I am writing this whilst sitting with my laptop watching the end of a cricket test match between New Zealand and South Africa.

I am also in day 5 of isolation, suffering a Covid19 infection, and New Zealand have to survive 270 balls with their last wicket to save the test match with a draw and prevent a highly likely South Africa win.

Both of these scenarios speak to issues of finding value in procrastination and antifragility. Medicine and healthcare can learn much from this.

The definition I want to use for procrastination, in the context of antifragility, a concept expounded by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his confronting and impressive book ‘Antifragile,’ is giving time and space for events to take their natural course, without excessive intervention.

Antifragility is discussed by Taleb in over 480 pages, and I encourage you to take up the challenge of reading and wrestling with his commentary on important lessons for our volatile times, spoken by ‘the hottest thinker in the world’ (Sunday Times) and capable of having ‘changed my view of how the world works (Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Laureate).

That which is antifragile responds well to, and even encourages, volatility and manageable harms as a tool to improve and grow. Conversely, fragility hates volatility which tends to break it. And that which is robust simply remains solid and unchanged in the face of harm. Whether applied to individuals, communities, nations, organisations, systems or structures, most would favour being on a trajectory of dynamic growth and improvement. Yet the majority of these have not embraced the principles behind antifragility, of minimising big losses and maximising big gains, through both a practical and philosophical investment in the wisdom of the ages. This blog will not discuss antifragility much further; it would be disrespectful to Taleb’s treatise on this to attempt a ‘brief log’ (blog) on what has taken him a lifetime, and much writing and speaking, to define.

However, I do want to distill some of his prophetic philosophy to concentrate on the role of procrastination in medicine and healthcare.

But before that, cricket. Part of what is central to antifragility is time. And to fans and detractors of test match cricket alike, the game is long and slow (five days of battling, 40 wickets, 2700 balls to be bowled). New Zealand have a lot at stake currently in saving the test match by batting out the innings without losing their final wicket – if they survive 270 balls, each one bowled with skill, aggression and finesse by strike bowlers against ‘tail end batters’ (they are not in the team because they are good batsmen; they are bowlers), then New Zealand wins the test series and becomes the number one ranked team in the world.

But the odds heavily favour South Africa. They have captured 19 of New Zealand’s wickets so far, and have both time and balls to nab that one remaining batsman.

South Africa are likely to succeed and win if they apply the above concept of procrastination. Keep doing what they are good at doing without the excessive intervention of responding to every new shot offered by the batsmen. Eventually, skill and time will result in the outcome desired.

We in healthcare can learn much from this. We have skills and knowledge, but often lack the wisdom and willingness to embrace time and natural process to assist our care of patients. The temptation when faced with each new interaction with a patient, is to add another layer of intervention.

One of the great challenges is having a systematic protocol to determine when to intervene and when to leave well alone. Iatrogenic harm describes damage done through intervention, and this is evident in medicine, when our treatments themselves do damage, particularly more than the illness itself. This iatrogenic harm is much more prevalent and damaging than we in medicine like to acknowledge.

Clinicians and patients alike can have difficulty accepting the value in enabling a natural course to deliver better outcomes than excessive intervention. Doctors endure many years of rigorous training to be given license to treat. Patients invest at personal cost in the recommendations of their doctors, and expect a tangible treatment outcome as a result.

Here are some quotes from Taleb in response to this.

‘As always, the elders seem to have far more wisdom than we moderns - and much, much simpler wisdom; the Romans revered someone who, at the least, resisted and delayed intervention.’

‘There is a Latin expression festina lente, “make haste slowly.” The Romans were not the only ancients to respect the act of voluntary omission. The Chinese thinker Lao Tzu coined the doctrine of “passive achievement.”’

Procrastination is a natural defense; it allows things to take care of themselves and demonstrate antifragility. Of course, intervention is often a good thing when a person is having a myocardial infarct or has a malignant tumour, when that intervention is likely to improve quality of life. However, there are many examples of where natural processes can outperform intervention, and we clinicians, trained in intervention, often find this challenging to accept. A viral respiratory infection will not benefit from antibiotics, which can in fact, generate harm; an immune-competent body with time and rest will heal itself. An injured joint and the associated inflammatory response should drive the patient to avoid the offending activity, rest and support that body part whilst the body’s anti-inflammatory processes go to work, rather than rushing to radiologic and orthopedic interventions.

Our global experience of the Covid19 pandemic highlights the complexities of procrastination versus intervention. In the traumatic crisis of the early 2020-pre-vaccination period, health systems were rapidly overwhelmed with limited treatment options apart from what we clinicians call ‘supportive treatment’ (essentially this is procrastination, using oxygen, fluids, positioning, and occasionally steroids to support the body’s own failing response), and many countries were forced to triage treatment to favour those most likely to have a positive response, leaving the remaining to succumb to a distressing death.

Through unparalleled global coordination and focused effort, following long-established pandemic anticipation and readiness by health and academic research organisations, vaccinations became available in late 2020, at a time when new variants of the virus were emerging and adding further pressure to already depleted health, social, and financial systems. During this period of the virus’ rampant spread, public health measures including mask wearing, social distancing, improved hygiene practices, border closures, and mandatory isolation became the norm across the globe.

Many global citizens were introduced to the concept of ‘mandates.’ Such governmental, social and health directives aimed to lessen the impact of the pandemic on, firstly health systems, then social and welfare structures, and finally financial markets and sustainability. However, for many, and in different jurisdictions, the reach of these mandates was felt to be too far, resulting in dissent, protest, and active rebellion. I touch on some of this in my blog ‘To vaccinate or not…and the social contract.’

This is not a blog about Covid19; however, I did raise it at the beginning, as I am currently midway through my own infection experience. Unlike many who were/are in a less fortunate position, my infection is with a less aggressive variant, I am in good health, and have the social supports to isolate at home with rest, food and fluids, allowing the natural course of the infection to run. I am experiencing a mild level of distress and harm, I have been prepared for it through vaccination and good health management, and I expect, with time and no specific intervention, the natural course will see me well in a few days, with an enhanced immunity to Covid19.

Many, if not most of our population in New Zealand, with high vaccination levels and good engagement with public health recommendations, will share my experience. We need to protect our health and welfare systems to care for those who are at higher risk of harm from Covid19 infection, and target appropriate intervention at them.

A quick review of the treatment options trialed for Covid19 infections reveals a list of over 70 agents or classes of medicines being studied. A number of these have been proved more harmful than beneficial, or, at best, lacking in evidence for positive effect. The risk of iatrogenic harm from these however is high, as we know they can cause adverse reactions, and the data for benefit is currently lacking.

The application of this thinking can be found in the notion of NNT, the Number Needed to Treat. In statistical and critical analysis of the value or harm of a particular treatment/intervention, the concept of NNT assists in determining its value. It calculates the number of patients needing treatment to deliver value from that treatment to one person. A low NNT (perfect is 1) means the intervention is highly valuable, whereas a high NNT, many patients needing treatment to benefit just one, increases iatrogenic risk and suggests procrastination would be better. And here another statistical term is germane, NNH, or Number Needed to Harm, the inverse of NNT. The ideal intervention would have a low NNT and high NNH, that is, the treatment benefits most who take it and harms few of those who do.

For example:

- Surgical treatment of a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is high risk intervention, but the patient will probably die without it. Without intervention, the mortality rate approaches 100%, and with intervention, the risk of death after 30 days from all causes of mortality is around 22%. The NNT to gain benefit is low (78% are alive at one month thanks to surgery, that is, close to 1) and the NNH compared to those not receiving the surgery (virtually 100% mortality) is very high.

- Medical treatment with aspirin to prevent cardiovascular events such as strokes and heart attacks in healthy people has a high NNT (over 1700) but better NNT in those who are high risk due to a previous event (77). The NNH is high also (1300) but lower than the healthy population NNT, therefore not a good intervention in this group, but clearly of value in those with higher risk.

Considering the value of procrastination, application of statistical analyses such as NNT and NNH needs to be done in the context of different patient groups and their risk profiles. However, in a generally healthy and stable population group, non-intervention is often a better and wiser initial therapeutic approach. Of course, there are exceptions, such as reducing risk factors for a person with a strong family history of premature heart attacks, but, as with most heuristics, the exceptions prove the rule!

The reality of being mortal human beings is that, eventually, something will kill us. Many of the potential causes of death will not get us, but medicine often will try to target and treat these anyway. Not all men will die from prostate cancer; many will die with it, but from something else. However, treating that non-fatal prostate cancer with potentially harmful surgery exposes the patient to iatrogenic harm for little gain. Urologists have realised this and embraced the concept of ‘watchful waiting.’ Here they monitor a person with prostate cancer, allow time and tests to determine if more aggressive surgery is required, and only then embark on potentially harmful but life saving treatment.

Watchful waiting is an excellent example of procrastination as a wise therapeutic approach. Not all will benefit from the intervention, so ancient wisdom suggests we should wait for the natural course of events to identify those who need intervention, those who will have an improved NNT/NNH ratio.

In primary care, we clinicians often have the luxury of time and space to practice medical procrastination, whereas our hospital-based colleagues, working under pressure to discharge patients and clear beds promptly do not. Time and space are our therapeutic allies as we have the opportunity for continuity of care and relationship with patients in their communities. A wise teacher of mine once said, in the face of his GP students anxious about making mistakes, ‘No-one dies in General Practice.’ This was not an inaccurate and flippant remark, misrepresenting our safety record; rather he was saying that for most interactions, if patients are unwell, we usually have time to identify the cause and determine the treatment before a catastrophe occurs. That is, he was teaching us about the value of procrastination and cautious intervention.

Such principles underpin a global medical initiative called Choosing Wisely. Now 10-years since its inception, this campaign’s mission is to promote conversations between clinicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is:

- Supported by evidence

- Not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received

- Free from harm

- Truly necessary

This example of what I call ‘active procrastination’ sits most comfortably with me, as a clinician who has been trained in, and practiced, interventionist approaches to treatment for many years. With a careful and critical consideration of the evidence, a focus on minimising harm (a central tenet of the Hippocratic oath), and through empathic and patient-centred conversations, my therapeutic interventions should only be delivered when ‘truly necessary.’

Procrastination is often seen with a negative connotation; a simple definition is ‘the act of delaying or postponing something’ – valuing time and natural processes; other definitions add terms such as ‘failure,’ ‘irrational,’ and ‘adverse consequences’ to this.

The view of procrastination as a disease to be cured misses the inherent value of the practice, to give room for antifragility, and to learn to respond to signals, not just noise.

The volume of information we are now exposed to in modernity is transformative, and not necessarily always in a good way. This overwhelming access to knowledge promotes a risk of neurosis. One can feel an obligation to keep up with and respond to all the noise of this information, rather than pause, pace and filter the noise out to respond mainly to the signals, that information which matters. Noise should be ignored; it is the signal that requires a response.

Medical knowledge is a good example. The production of and access to medical information is expanding exponentially. According to a study in Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association the doubling time of knowledge in the 1950’s was 50 years; by 2020 in that study it was projected to be 73 days! And some experts suggest that only 5% of this new information is of direct clinical importance, that is, 95% of all this new knowledge is noise and should be filtered out. The challenge is how to do this refining work, because, make no mistake, it requires intent and effort.

In our respective fields of training and expertise, we each carry a responsibility to critically appraise information which impacts our area of specific knowledge. Such appraisal draws on what we already know, where we know the gaps to be in knowledge, a willingness and ability to think and dig below the surface appearance of information, and, as Taleb promotes, trust knowledge that has stood the test of time.

Without intending to be too reductive regarding Taleb’s principle, an example from Covid19’s recent past is that the initial thrill of excitement that a new use of chloroquine would be an effective treatment, quickly faded, whilst the age-old strategy of mask wearing in a pandemic, although initially discredited by many, has stood time’s test of effectiveness.

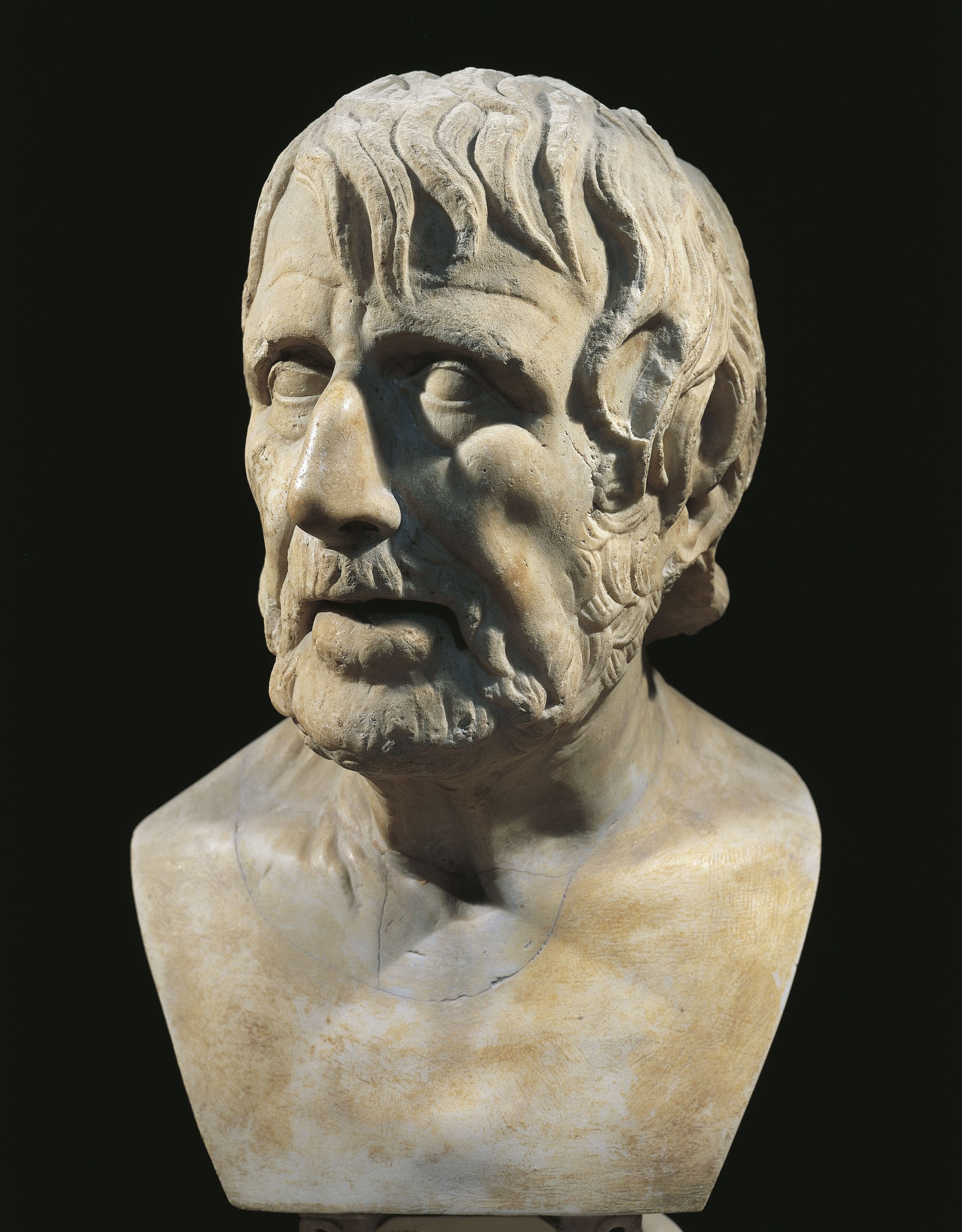

Taleb highlights an ancient source of wisdom who’s teaching remains relevant today, the Roman businessman and philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca.

Seneca was the wealthiest person in the Roman empire and a stoic philosopher (you could argue that it is easy to promote stoicism – indifference to fate, harmony with the cosmos and denigration of earthly possessions from a position of wealth and power, but let’s focus on his teaching which has endured in value to modernity). ‘Wisdom in decision making is vastly more important, not just practically, but philosophically, than knowledge.’

In fact, it was Seneca’s view of the value in keeping wealth that moved him beyond traditional stoicism which valued robustness, to embrace the principles of antifragility. Seneca’s perspective was that an intelligent life is all about emotional positioning to eliminate the sting of harm. For example, Seneca had a regular practice of mental exercises to write off his possessions, so if losses occurred, the sting would be less intense; he would embark on a journey with only the barest possessions as if he had been shipwrecked. Seneca also invested in social deeds; things can be taken away, but not good deeds and acts of virtue. Seneca said ‘Wealth is the slave of the wise man and master of the fool.’

Taleb makes the comment: ‘If you want to accelerate someone’s death, give him a personal doctor.’ The context of this statement is that he believes doctors are driven to excessive intervention, which results in greater harm than good. My revision of his comment is that you should seek a doctor who understands the role of procrastination in health care and the value of appropriate levels of intervention.

This painting by Luke Fildes titled ‘The Doctor’ speaks powerfully to me of these principles. The image bears an unwell child, distraught parents seeking divine assistance, a doctor sitting passively by, with discarded prescriptions and empty medicine containers as evidence of failed interventions. Only time can bring healing now, as the light and hopeful promise of new dawn enters the room, and the presence of loving parents and a caring doctor wait.