The World Organisation of Family Doctors (WONCA) Asia Pacific Conference for 2026 in The Philippines invites applications for its Policy Pitch Contest with the following details:

Theme:

Translating Family and Community Medicine Research into Policy

Objective:

This competition aims to engage medical students, trainees and family physicians in policy-oriented discussions by challenging them to present research findings relevant to family and community medicine in a compelling and actionable manner. It provides a platform to bridge the gap between research and policymaking by encouraging students to articulate how their work can influence healthcare policies and community health programs.

I decided to apply for this 3-minute platform with the abstract from my recently published work titled ‘A wholistic approach to patient-empowered care.’

In the same month I read the cover story article in the NZ Listener titled ‘Curing Health’ with the tag line ‘Life Support – the answer to our healthcare crisis may lie less in increasing the supply of doctors and nurses and more in reducing demand for hospital beds.’

This blog will not explore many of the issues raised by a multitude of better-informed writers and researchers than me, many of whom are referenced by the Listener writer Danyl McLauchlan. Rather than a full treatise on what ails the New Zealand health system, which can be found elsewhere, this blog will focus on one – albeit powerful – solution.

McLauchlan's article quotes the Nobel Prize winning economist Angus Deaton: "Physicians are a giant rent-seeking conspiracy that's taking money away from the rest of us, and yet everybody loves physicians. You can't touch them." Provocative stuff! The term rent-seeking means taking money without adding value. Deaton’s primary message is that we need to tackle rent-seeking (where “talent is devoted to stealing things, instead of making things”) to build a “fairer, more equal society without compromising innovation or entrepreneurship.” In part, Deaton is referring to the US health sector, which has a completely different funding system than NZ. However, his challenge that economic and health structures which direct profits or value 'upwards' away from the workers and users will result in failure is relevant in the NZ context. Our system has a combination of public and private funders; as healthcare costs increase with a limited public budget, opportunities for the private sector to gain dominance increase, with the attendant risk of rent-seeking.

So, the question - the key puzzle piece - is how to operate in an environment where privatization exists whilst creating value for all.

McLauchlan describes a bottleneck to care and access to medicines in the NZ health sector which is caused and justified by notions of patient safety. Medical diagnosis has complexity; medicines are potentially harmful; surgical interventions are not benign. Ensuring that patients consult with appropriately trained and resourced medical professionals in a timely manner allows their health care to be safe.

There is a paradox in a failing system under pressure where such bottlenecks are increasing risk. Advances in medicine come with gains and costs. People have the opportunity to live longer with diseases which can be treated through surgical and medical innovation. Such progress places pressure on funding systems which have limited budgets and require more intensive processes – from assessment and investigation to diagnosis then treatment, monitoring and managing outcomes, both positive and negative. If the healthcare system does not resource providers of these services well, then the demand for care will outpace the capacity of the system to provide such care. The consequent risks of this imbalance include:

- Demand pressures meaning people who are unwell defer accessing care until their conditions worsen, requiring more costly treatment.

- Such delayed care for worsened conditions will often have poorer outcomes than earlier intervention.

- This erodes public confidence in the health sector to deliver quality services.

- The workers in this health sector become frustrated and dissatisfied with their roles.

- Investment in the sector risks targeting populist short-term projects over long term, less headline-grabbing programmes which may be more impactful.

- Inequity increases, as those who can afford private care resource this sector, whilst those who cannot languish with poorer outcomes in an under-resourced public system.

The most cost-effective, equitable and accessible care is preventative and in primary rather than secondary health sectors.

The nature of prevention is most of its work and impact takes place outside of the health system, through good lifestyle choices such as diet, activity, smoking and other substance avoidance, quality sleep, and meaningful engagement in work and family/social settings. Some touch on the health system with medically focused endeavours such as vaccination, disease screening and monitoring of risk from family history or environmental exposures.

This requires people to have sufficient motivation, awareness, and tools to participate in their own prevention care.

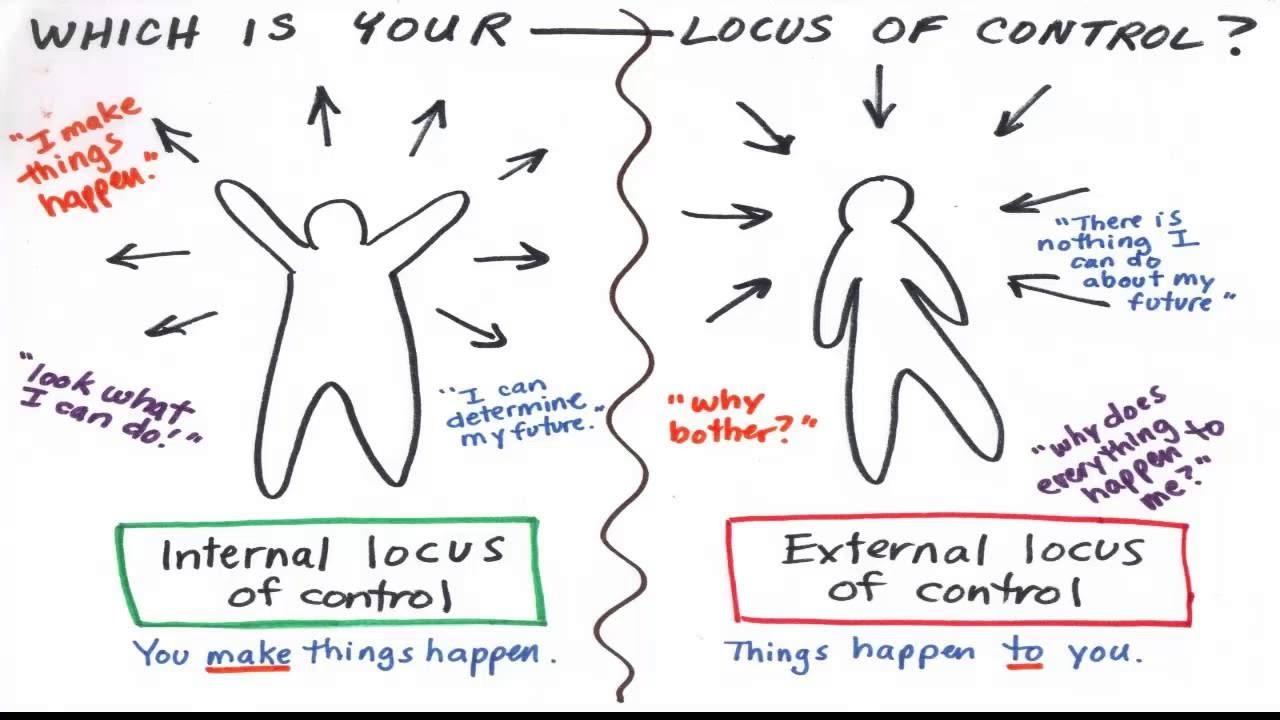

Relying on the medical system to provide such care will fail – due to the issues discussed around access and the reality for many, if not most, that shifting locus of control from patient to doctor will erode the sense of responsibility the patient feels for their own prevention care.

I see many patients who want to change unhealthy lifestyles, for issues such as weight loss, smoking cessation or to reduce their risk of a heart attack. They seek ‘a pill’ as making changes in their own lives is ‘too hard’ – for a range of reasons.

This speaks to the locus of control challenge. If a person’s sense of capacity to change something in an effective and sustainable way is low, it will be ‘too hard’ and they will seek the intervention of a controlling agent outside of themselves. However, with high ‘self-efficacy’ a person can be the ‘project manager of their own life’ – to coin a phrase from Positive Medicine – they hold the locus of control and much evidence demonstrates this results in healthier outcomes, both in prevention and in medical care.

NZIER’s Sarah Hogan suggests in McLauchlan's article that the solution lies in a ‘shift away from the constraints of the current system’ which includes a revision of the dominance of GPs delivering primary care.

My obvious bias here is that I am a GP (General Practitioner) who has spent his whole career engaged in and advocating for the value of well-trained medical professionals operating in a sufficiently resourced environment being the most effective diagnosticians, treatment-providers, care-coordinators and gatekeepers of the public health purse.

However, I agree with Hogan’s statement, although not with her sentiment, that delivery of primary care needs to be revised (her words are ‘shift away from’).

Rather than see GPs as the dominant force in primary care delivery, I propose the more effective and powerful force lies with the patients themselves. This is the key puzzle piece. We in the healthcare system need to encourage this locus of control to shift away from the medical team and back to the patients.

Here is a challenge, although not an insurmountable one. The value of ‘patient safety’ is a highly held one in medicine, and appropriately so. The Hippocratic maxim ‘first do no harm’ has obviously stood the test of time and should continue to do so. However, our system is harming people, and those of us who have some degree of influence, let alone those participate in it, have an obligation to commit to change. A positive disruptor in the New Zealand context is GP and poet Dr Glenn Colquhoun. Glenn co-led a nationwide call for health reforms in early 2025, the Hikoi for Health. His colleague Dr Art Nahill states "(t)he health system is badly broken," and the purpose of this project is "to let people know that the heath system can and must be changed."

This notion of patient safety has entrenched thinking, behaviour and policy which has contributed to the Cost Disease issue. Examples of this include:

- Requirement to see a GP every 3 months for a medication prescription. This is soon to change for patients with some stable long-term conditions.

- Limiting access to transformative treatments in areas such as mental health, obesity and dermatological conditions due to requirements for ‘specialist’ involvement. Many GPs are specialists in their field of Primary Care and have appropriate skills to reduce such barriers to care.

- Clogging up hospital outpatient clinics with patients who could, with adequate funding, resources and supports, be appropriately followed up by their GP team.

Perhaps the safest care for patients is to not disempower them in their own healthcare journey; rather, resource and support them to be the ‘project manager of their own health.’ A key here is the current definition of health as 'the ability to adapt and self-manage.'

My recently published work on such a model – ‘A wholistic approach to patient-empowered care’ – explores how to resource, conduct, measure and review what I have called an ‘Abundance Model of Healthcare,’ and which others on a similar journey have called ‘Positive Medicine,’ ‘Te Whare Tapa Whā,’ and ‘Positive Psychology.’

The concluding statement from the article says: 'In the current resource-constrained primary care environment, with access barriers to general practice care such as cost, clinician availability, and limited consultation time, consideration of alternative models is a necessary strategy for effective, efficient, and quality health care. The model presented in this paper requires limited investment, harnesses the power of the patient, and offers the clinician the opportunity for professional satisfaction as a guide and mentor.'

If a revision of the delivery of primary care were to place patients at the true centre of the model, with less reliance on GP services, adequate resourcing for education in health literacy, access to home-based tools for disease monitoring, meaningful support services, and sufficient incentivisation, then the following might occur:

- Less demand for GP clinic appointments because patients are self-managing.

- Improved access to GP services for those who need them in a timely manner.

- More efficiency in the economics of healthcare.

- Better health outcomes for patients.

- Professional satisfaction and resilience in the healthcare sector.

So, Deaton's concern that talent is being used to steal rather than make things, has, in the health context, a powerful foil. If those of us who are invested in the system - whether medical professionals, business owners, funders and policymakers, or patients - agree that the greatest value will be found in a healthy patient - one who is resourced to adapt - then we have a system which has made something of great value out of talent.

To quote Danyl McLauchlan’s final statement:

‘Economics, however, is constrained by politics – which usually prevents significant change to the status quo. But with health, political inertia is coming into conflict with patient lives, and a growing public clamour for serious change.’

I hope to have the opportunity to present my 3-minute ‘Policy Pitch’ in response to this clamour for serious change. I hope to find ears, not just at our regional WONCA conference, but at the desks, caucus tables, and executive boardrooms of our politicians, and move their inertia to healing change.