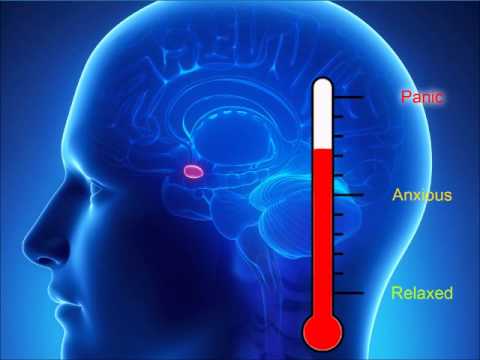

When the brain is under stress, the body releases cortisol, our stress hormone, which drives adrenalin to course through our body, raising heart rate and breathing, priming muscles with fuel for action, and engaging the reptilian part of the brain, the amygdala, to take over with shutting down of digestion, reproductive processes, the immune system and rational thinking. The purpose of this process is to devote energy to the stress response, and temporarily limit the activity of unnecessary body functions.

This is all highly relevant for the crisis of escaping a burning building or rescuing a drowning child, but rather less functional for the day to day stressors of work pressures, driving and responding to unwanted social media notifications.

In moments of stress or panic, we are not always at our peak. To be better prepared for this, concepts of ‘Prospective Hindsight’ or a ‘Pre-mortem’ (as compared to a post-mortem) whereby we can anticipate a stressful event and put systems in place, not to prevent but rather to influence our response and the events impact, can enable a powerful life-survival strategy.

This all makes rational sense, but the paradox of prevention is that people will highly prioritise treatment but not prevention, a great frustration for those of us working in primary health care.

A ‘Commitment Device’ is a tool whereby a behaviour or system is put in place to prevent an adverse outcome. It's role is further explored in interviews with Guy Raz on the TED Radio Hour. For example, this may be choosing to not walk down the confectionary aisle at the supermarket to avoid poor weight management; or the use of a workplace ‘swear jar’, where poor language choices are penalised with a fine; or planning the order of phone call in a car accident – police, partner, doctor, insurance company.

Such commitment devices are needed because temptation is hard to resist, as the future tends to be trumped by present gratification, and sometimes, as discussed above, the reptilian brain does not allow us to think clearly in a crisis.

An ancient example of this is found in the epic ancient poem by Homer, Odyssey. In the poem, the Greek hero Odysseus is returning home and has to sail past the land of the Sirens, whose enchanting song draws sailors and their ships to be wrecked on the rocks. Odysseus is aware of the risk, and his commitment device, due to his desire to hear the Siren’s song and survive, is to tie himself to the mast of his ship, while the sailors plug their ears with wax.

The health applications of this thinking are obvious, with a few examples.

Neuroscientist, Lisa Genova, who is an author, with her first novel Still Alice now a movie starring Julianne Moore, writes about the impact of Alzheimer’s Disease. We now understand the role of amyloid beta in the accumulation of plaques that disrupt brain function in the disease. Such plaque deposition can be prevented, and its impact mitigated by certain behaviours.

Prevention is achieved by lifestyle strategies that benefit many other diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and various cancers. These lifestyle measures include healthy, plant-predominant diets, regular exercise, good weight management, and quality sleep. Sleep is particularly valuable for the brain in that it gives time for the important glial cells, where amyloid deposits accumulate, to be rinsed by cerebrospinal fluid, being cleansed and refreshed.

Once the amyloid plaques start, their impact on brain function can be delayed through a process of creating ‘Cognitive Reserve’. Here brain cell connections, or synapses, are made more numerous and resilient through neuroplasticity. The ‘Nun Study’ demonstrated the power of this, and such cognitive reserve is achieved through learning and nurturing social supports.

Dan Goldstein is a cognitive psychologist, and he has explored the question of how to imagine our future selves in the present to enable better commitment devices or behavioural changes. One of his studies in encouraging saving for retirement found that using a picture of someone in the future assisted their imagination for their future self and motivated improved saving behaviour.

Here is a powerful application for prevention strategies in health. Perhaps we doctors and nurses, as health promoters, could motivate health behaviour change by giving patients an image of themselves in the future. Seeing themselves in the future may well assist in achieving those lifestyle changes that otherwise seem less of a priority in the present.

By harnessing this tool for imagination (even if it makes us face an uncomfortable reality!), we can make the future more relevant.